The State of Digitalisation in EU Agriculture: What the Data Finally Shows

- Adoption today: digital basics are widespread, advanced tools are not

- What farmers adopt, and what they clearly do not

- The software layer is where momentum actually exists

- What actually drives adoption

- Data practices: broad collection, cautious sharing

- Who adopts more, and why

- What this baseline really tells us

- Where to explore the data

How digital is EU agriculture?

Until recently, nobody could answer that question with evidence. Digitalisation has been a central pillar of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and of the EU Digital Agenda for years, yet there was no EU-wide baseline to measure where farms actually stood.

The Joint Research Centre (JRC) has now filled that gap. Its report The state of digitalisation in EU agriculture: Insights from farm surveys (JRC141259) is based on 1,444 interviews with farmers in nine Member States (Germany, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Lithuania, Hungary and Poland), conducted between June and October 2024. This is the first systematic snapshot of farm-level digital adoption across the EU.

What follows is a narrative reading of the report’s core results, combining key figures, selected charts, and the implications that matter most for policy makers, technology builders, and anyone thinking seriously about AI in agriculture.

Adoption today: digital basics are widespread, advanced tools are not

The first result is unambiguous: most farms are connected and digitally equipped at a basic level.

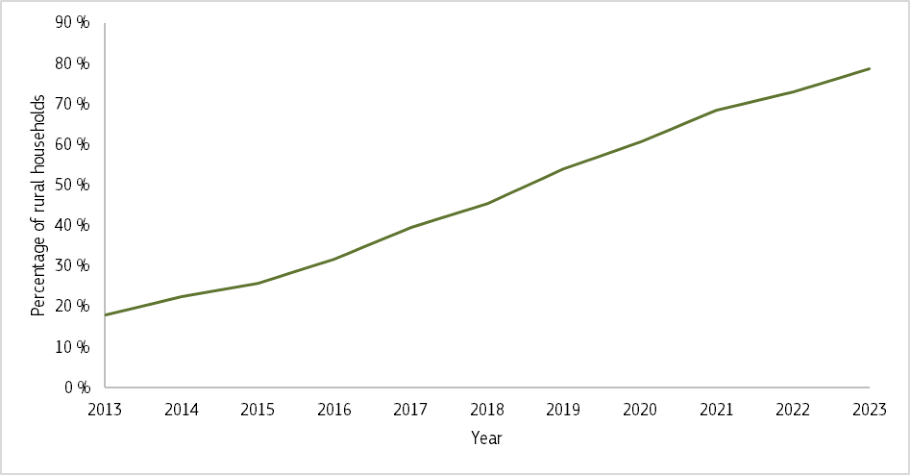

Around 85% of surveyed farms report adequate internet coverage on the farm and in the field, while 15% still face connectivity constraints. Smartphones and general-purpose digital devices are widespread. The problem is not that farmers are offline.

The real divide is between general IT tools and production-specific digital technologies.

About 93% of farms use at least one general digital tool such as accounting software, weather apps, trading platforms, mobile apps or communication tools, and 68% use three or more. These tools are familiar, affordable, and perceived as useful.

By contrast, adoption of crop-specific and livestock-specific technologies remains limited and uneven. For most specialised tools (drones, GNSS tractors, yield mapping, sensors, automatic milking), adoption rates range between 3% and 23%, depending on the technology. While many farms report using at least one crop-specific (79%) or livestock-specific (83%) tool, only 29% use three or more crop technologies and only 17% three or more livestock technologies.

The distribution of total digital adoption is shown below.

Number of digital technologies adopted by the farmers surveyed (%). Source: JRC

Adoption increased rapidly between 2008 and 2020, but has slowed since 2020. Intentions to adopt new technologies over the next five years are modest. The report links this slowdown to cost pressures and economic uncertainty.

The picture that emerges is stable but uneven: the digital foundation is there, yet the layer of advanced, production-focused technologies remains thin.

What farmers adopt, and what they clearly do not

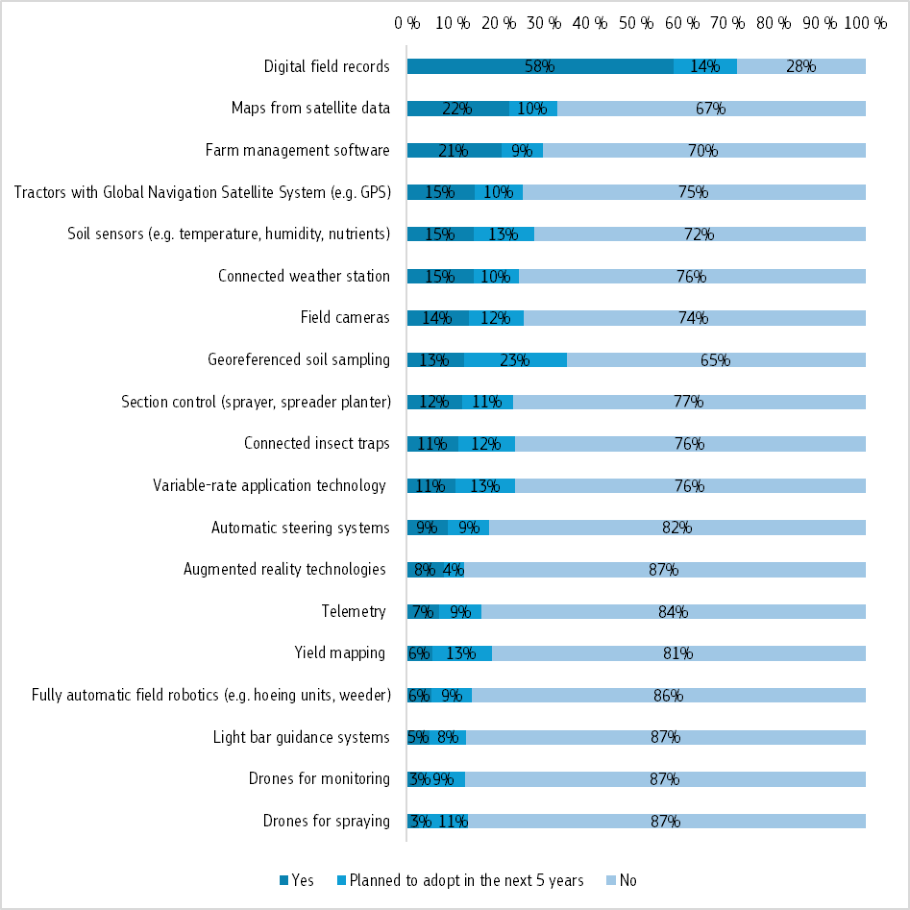

The report avoids normative labels, but Figure 15 and Chapter 4.3 make adoption patterns very clear.

Farmers adopt technologies they see as affordable, understandable, and directly useful. Technologies that fail on these dimensions remain marginal, regardless of how prominent they are in public discourse.

Among crop-specific technologies, adoption is led by digital field records, used by 58% of respondents. Next come satellite-based maps (22%) and farm management software (21%). At the bottom sit drones, both for monitoring and spraying, each adopted by only 3% of farms. Crucially, 87% of farmers report no intention to adopt drones in the next five years.

Automatic steering, telemetry, yield mapping, field robotics and light-bar guidance cluster between 5% and 9%. Planned adoption is modest for most tools, typically an additional 9 to 15% over five years. One notable exception is georeferenced soil sampling, which rises from 13% today to 23% planned, signalling interest in precision soil data.

Adoption rates of crop-specific digital technologies (%). Source: JRC, Chapter 4.3.

The livestock side shows the same structure. Digital livestock records dominate (66%), while cameras, sensors and automation tools lag far behind.

The implication is not that drones or robotics lack value. It is that their value proposition does not scale across farm types at current cost and complexity levels.

The software layer is where momentum actually exists

Across both crop and livestock systems, management software and digital records sit in a clear adoption sweet spot. These tools are perceived as affordable and useful, and they address a major pain point: administrative burden.

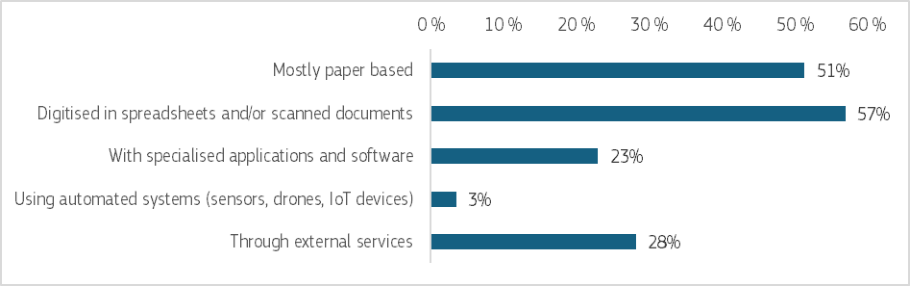

Data collection and management on farms remain largely manual or semi-digital. Paper records, spreadsheets and scanned documents are common. The report explicitly notes that better digital tools could reduce administrative workload and improve interoperability with advisory services and compliance systems.

This aligns tightly with observed adoption. Farmers expand on the software layer they already trust, rather than jumping to expensive hardware. From a technology and policy perspective, this is the clearest signal in the report: platform-centric, software-first solutions match actual demand.

Hardware-heavy technologies, by contrast, face structural friction. Drones, robotics and advanced machinery are expensive, sometimes regulated, and often poorly tailored to diverse farm sizes and production systems. As a result, their adoption remains niche in the medium term.

What actually drives adoption

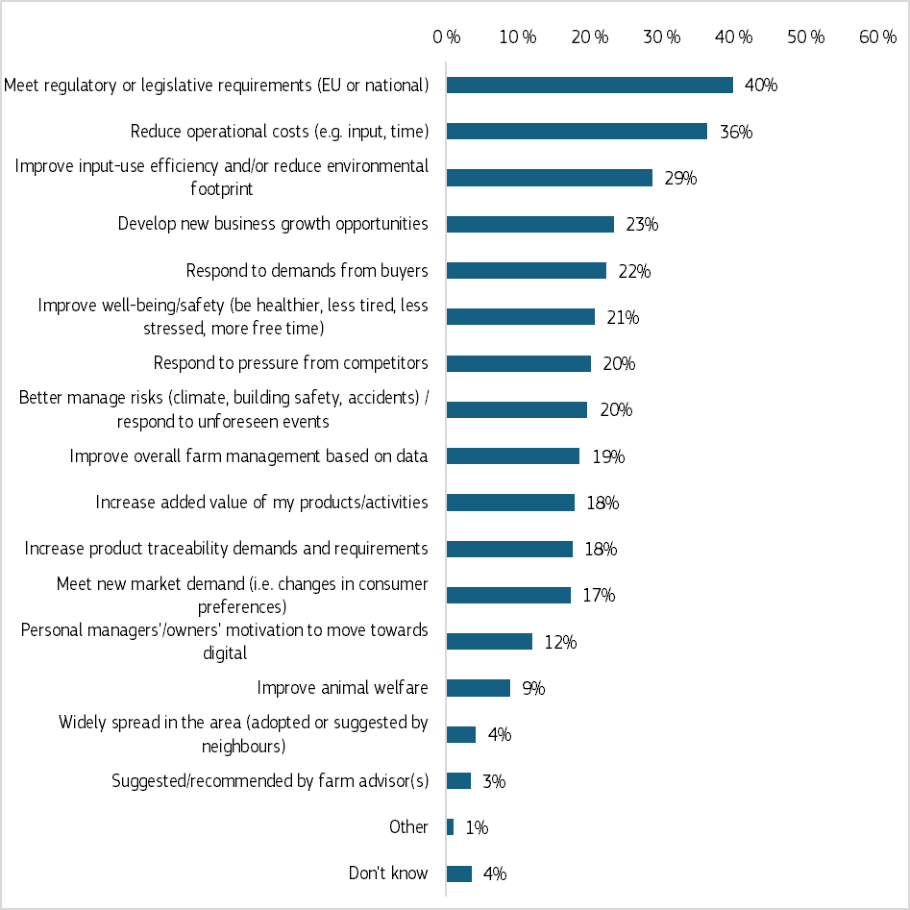

When farmers are asked why they adopt digital tools, five drivers dominate: efficiency gains, cost savings, regulatory pressure, quality of life, and market pressure.

In the report’s econometric analysis, farmers citing these drivers adopt between 8% and 38% more technologies. Reported barriers include high costs and limited digital skills, but these barriers are less strongly associated with adoption outcomes than the positive drivers.

Public authorities and cooperatives play a relatively small role in triggering adoption. Most uptake is driven by farmers themselves and by close value-chain actors. This suggests room for better-targeted public support.

Main barriers to digital adoption (%). Source: JRC

Data practices: broad collection, cautious sharing

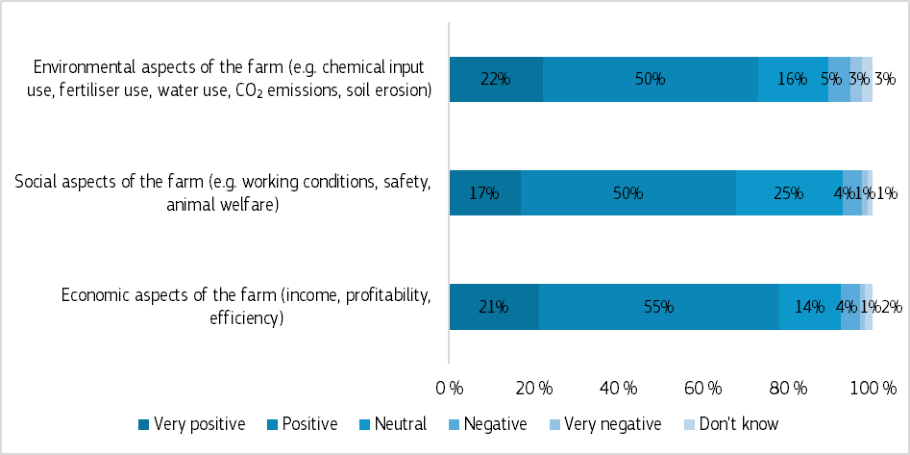

Farms collect a wide range of data, from financial records to soil, livestock, and input use. Collection frequency varies, but the real bottleneck is how data are managed. Manual and semi-digital processes dominate, reinforcing administrative burden.

Electronic data sharing is selective. Many farms do not share data at all. Those who do mainly share with trusted actors such as advisors, cooperatives and other farmers. Banks, technology firms, researchers and public administrations are much less common recipients.

Concerns about data privacy, security and control dominate. Farmers share data primarily when they see clear indirect benefits, such as better advice or tailored services.

Frequency of farm-level data collection (%). Source: JRC

Electronic data sharing with external actors (%). Source: JRC

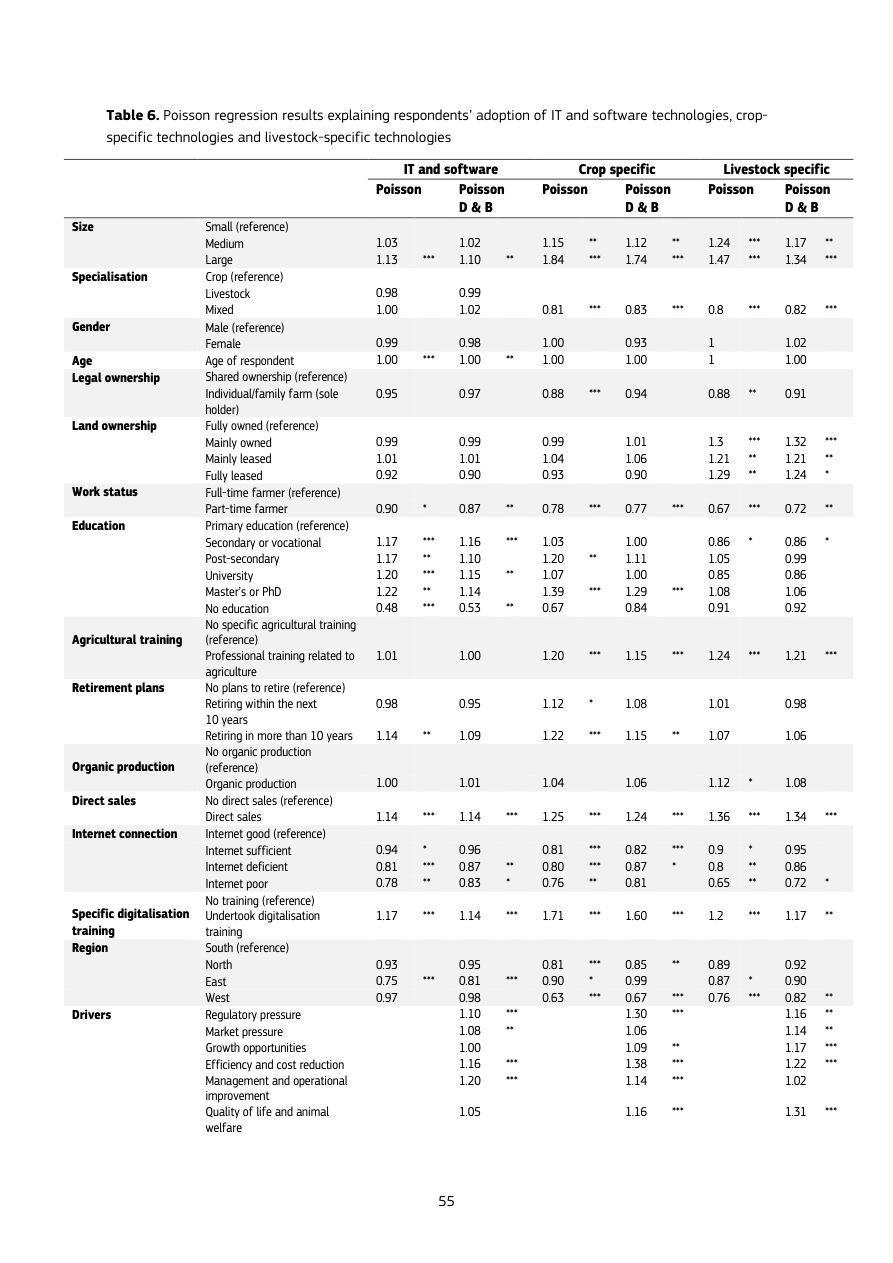

Who adopts more, and why

Regression analysis confirms familiar patterns. Larger farms adopt significantly more technologies, between 10% and 84% depending on category. Poor connectivity is associated with 4% to 30% fewer technologies. Direct sales, full-time farming, and specialised training are all positively associated with adoption.

Age plays a limited role. Education matters more for general IT than for specialised technologies. Gender, legal form and organic production are largely insignificant.

Poisson regression results for digital adoption. Source: JRC

What this baseline really tells us

The report does not point to a single policy lever. It points to heterogeneity. Adoption differs by technology, farm size, region and production system.

The strongest signals are clear:

- Connectivity and training matter

- Administrative burden discourages adoption

- Software and records deliver visible value

- Data trust is a prerequisite for AI and advanced analytics

For AI in agriculture, this baseline is especially important. AI adoption will depend on the same factors: cost, perceived benefit, trust, and fit with farm realities. The data suggest a software-first pathway, where AI augments management, compliance and decision support before it drives robotics or full automation.

Where to explore the data

This post draws from selected figures in the report. The full dataset can be explored interactively by country, farm size and technology type via the JRC dashboard:

JRC DataM: Digitalisation in EU Agriculture

https://datam.jrc.ec.europa.eu/datam/mashup/DIGITALISATION_IN_EU_AGRICULTURE/

Reference

Tur Cardona, J. et al. The state of digitalisation in EU agriculture: Insights from farm surveys. Publications Office of the European Union, 2025.

DOI: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/4688498

This is now the empirical baseline for CAP implementation and for the Commission’s work on a digital and AI-ready agri-food sector. The signal is consistent throughout the data: records and software first; drones and robotics when they demonstrably earn their keep.

If you found this useful, please cite this as:

Rossetti, Simone (Jan 2026). The State of Digitalisation in EU Agriculture: What the Data Finally Shows. https://rossettisimone.github.io.

or as a BibTeX entry:

@article{rossetti2026the-state-of-digitalisation-in-eu-agriculture-what-the-data-finally-shows,

title = {The State of Digitalisation in EU Agriculture: What the Data Finally Shows},

author = {Rossetti, Simone},

year = {2026},

month = {Jan},

url = {https://rossettisimone.github.io/blog/2026/the-state-of-digitalisation-in-eu-agriculture/}

}

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next:

Subscribe to be notified of future articles: